Peter Sterry, fast sermons and Quakerism

So I am sitting at my desk at work when a friend, who has an even bigger obsession with books than me, wanders over and says, “Do you know about Wing numbers?”.

“Um, yes. Why?”

“Can you look one up for me?”

“Yes, okay.”

I open up ESTC and find the short title, then look it up on EEBO. It’s a sermon called The Spirits Conviction of Sinne, preached by Peter Sterry in 1645. While I am doing this, my friend gets out a bound octavo book and opens it up to the same title page that I’m looking at on EEBO.

“When’s your birthday?”.

“July”.

“Happy birthday!”, he says, and passes the book to me. It turns out it is a collection of Sterry’s sermons to Parliament during the 1640s and 1650s, together with a few other surprises too.

Now I am obviously very lucky to have friends who see collections of seventeenth-century sermons and immediately think “I know who would like that”. As an inadequate token of gratitude I did some digging into the provenance of the collection and thought it would be interesting to share it.

The five sermons by Sterry that the book includes are:

- The Spirits Conviction of Sinne. Opened in a Sermon before the Honorable House of Commons [26 November 1645].

- The Teachings of Christ In The Soule. Opened in a Sermon before the Right Honble House of Peers, in Covent-garden-Church [March 29, 1648].

- The Clouds in which Christ Comes. Opened in a Sermon before the Honourable House of Commons [27 October 1647].

- The Comings Forth of Christ In the Power of his Death. Opened in a Sermon Preached before the High Court of Parliament [1 November 1649]

- England’s Deliverance From the Northern Presbytery, compared with its Deliverance from the Roman Papacy: or A Thanksgiving Sermon Preached [5 November 1651].

This is not every sermon Sterry published, but it is nearly all of them. And they are all significant sermons: placed together, they tell something of the story of the puritan victories of the 1640s and the growth in religious radicalism that the same decade saw.

The first three are fast sermons. These had become established as a Parliamentary tradition by the 1620s and were significant in the 1640s as a venue where preachers favoured by Presbyterian and Independent grandees could be used to fly religious and political kites to an audience of MPs or peers. They stopped in 1649, at least as regular sermons, but extraordinary fast sermons carried on after that date.

The 1645 sermon is the first one Sterry ever preached to Parliament. He was chaplain to Lord Brooke, who along with other disaffected peers like the Earl of Warwick and Lord Saye and Sele had played a significant role in leading Parliamentary opposition to Charles I during the early 1640s. Brooke was shot by a sniper while laying siege to Lichfield Castle in 1643. After that, Sterry became part of the Westminster Assembly of religious divines. The sermon is fairly conventionally puritan, in that it focuses on the role of the holy spirit in redeeming the chosen. But it’s sold by Henry Overton and Benjamin Allen, booksellers with more radical sympathies. Both were partners based in Cripplegate.

The Clouds in which Christ Comes is the first sign of Sterry moving in a more radical direction. It dabbles in the mysticism of Jakob Boehme, who was a German theologian who had various personal experiences of God. It was delivered at a critical time for the Parliamentary side: a coup by the Presbyterians had been seen off but the Independents were now having to deal with Leveller influences in the army. The Putney debates started the day after this sermon was delivered. As a result, the text is rather apocalyptic. The Teachings of Christ In The Soule was preached at a time when Parliament’s relationship with the Scots had broken down, and both were preparing for war. It also shows signs of being influenced by Boehme. Both texts were sold by Robert Dawlman, a specialist in theological literature with a shop in St Paul’s Yard.

The Comings Forth of Christ In the Power of his Death marked Cromwell’s victories at Drogheda and Wexford. By this stage Sterry was preacher to the Council of State, the executive body set up after the death of Charles I which included Cromwell and various of the Independent and New Model Army grandees as its members. It was much more overtly millenarian than Sterry’s previous sermons. England’s Deliverance From the Northern Presbytery marks the defeat of the Scots at Worcester, and argues that this is a greater deliverance for England than having rid itself of Catholics.

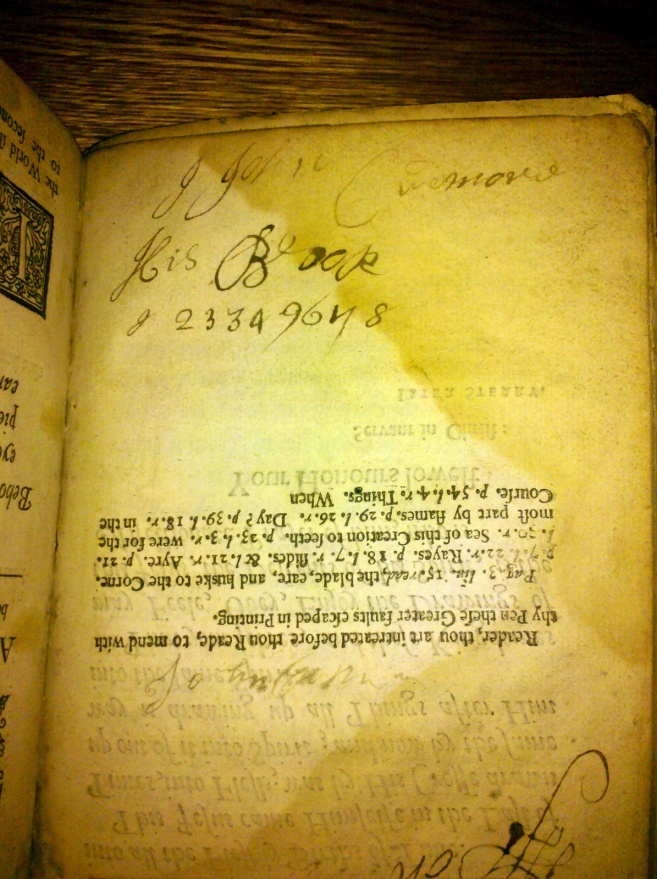

The fact that all of these texts were collected in one place indicates someone with a significant interest in Sterry and the radical, millenarian end of puritanism. It is not clear when they were gathered together. The collection is labelled as being bound bound by L. A. Smart, a binder in Gloucester. It seems this was Lucy Ann Smart, who was in business from at least the 1870s onwards, but the binding does not necessarily indicate the date of collection. Nevertheless, I suspect this may well have been the late nineteenth century. Some of the texts have marginalia, and this is not all in the same hand, suggesting they were probably not all collected by one person during the seventeenth century. The Clouds in which Christ Comes has this after the preface, which would appear to be a seventeenth-century hand:

(Incidentally I cannot make out John’s surname and would welcome any help with this).

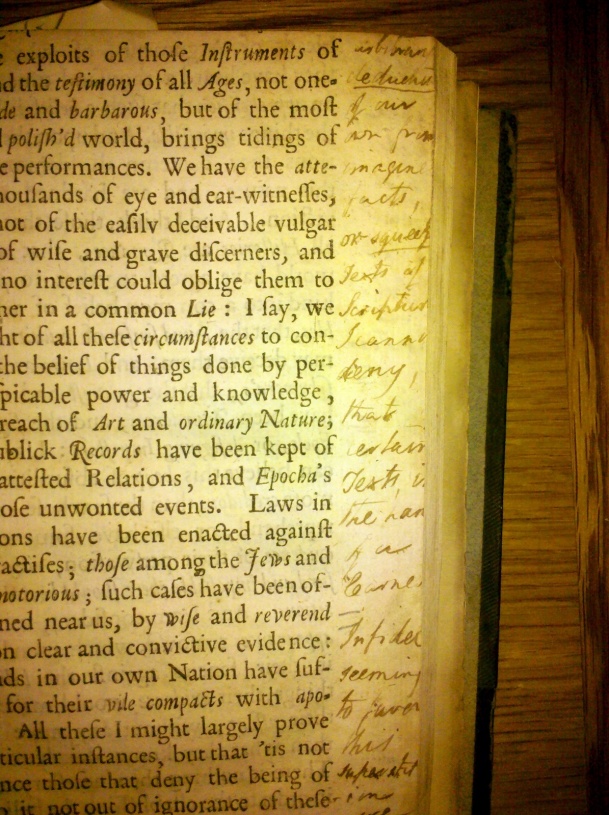

This book is in the worst condition of them all: it is damp stained and missing the second half. A reader – I am not sure it’s the same one as John – has also been through and corrected the text at various points, in line with an errata page inserted by the printer:

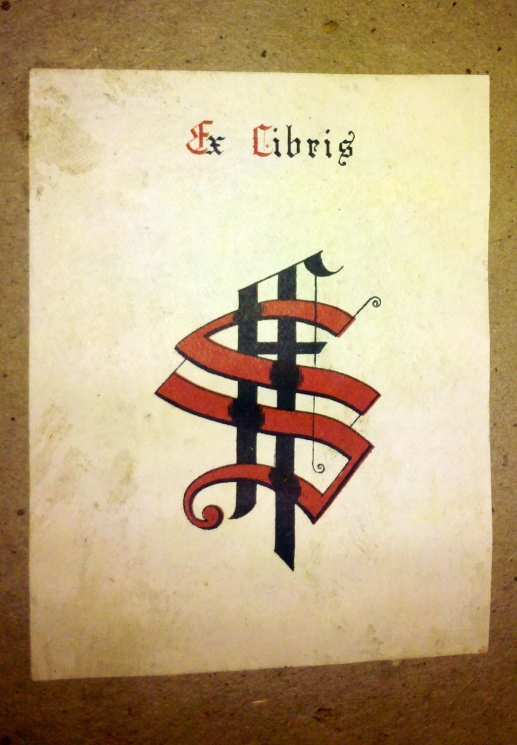

This particular text also has a bookplate (which I have not been able to identify – again, I would welcome any thoughts), whereas none of the others do, which makes me wonder if this one at least came from another collection:

Whereas another text bound in with the Sterry books has extensive marginalia in what I think is a different and later hand:

There is also the question of some additional texts, by authors other than Sterry, that have been bound together with Sterry’s sermons. The three additional texts are:

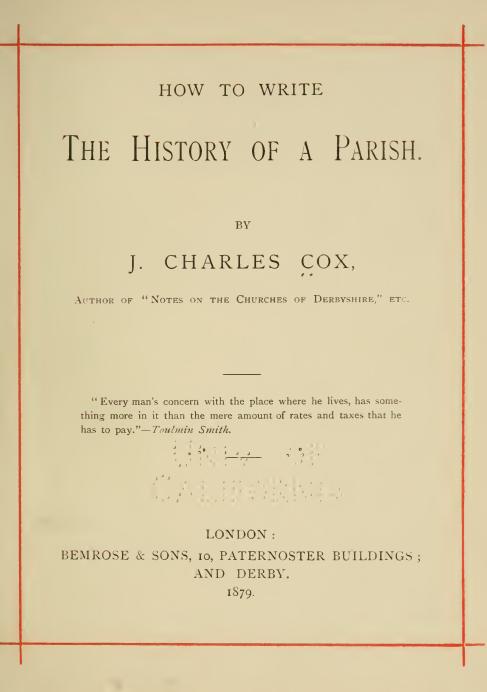

- The preface to Saducismus Triumphatus by Joseph Glanvill. This was published in 1681, after Sterry’s time, and affirmed the existence of witches at a time when learned opinions were not inclining that way.

- A Victorian reprint (1894) of William Dell’s Doctrine of Baptisms. Dell was, like Sterry, an alumnus of Emmanuel College, Cambridge and another radical preacher, associated with Thomas Fairfax. He was critical of baptism of children.

- Another Victorian reprint (1864) of Ralph Cudworth’s The True Knowledge of Christ. Cudworth was another Emmanuel alumnus, and this particular sermon sermon argued against blind adherence to rituals, stating that true Christians were to be spotted by how they lived their lives.

Certain Puritan preachers of the mid-seventeenth century enjoyed a renaissance in the nineteenth century due to interest from nonconformists, who were quick to see parallels with their own beliefs. Sterry in particular had preached in 1656 – at the time of the controversy over James Nayler – about the need to treat Quakers kindly. The similarity between the concept Sterry had of the holy spirit, and Quaker views on the inner light, means that Victorian Quakers were probably able to absorb his works fairly easily into their own worldview.

The likelihood of it being a Quaker who collected these sermons is increased when one realises who the printer of the two reissued sermons was: John Bellows in Gloucester, who was well-known to contemporaries in south-west England as a Quaker. So it seems likely that the books were collected by a Quaker connected to Bellows in some way, or who was at least from Gloucestershire or the surrounding counties. Beyond that, though, I’ve drawn a blank.