Killing Noe Murder

I’ve been reading Edward Sexby’s Killing Noe Murder for class this week, and it got me thinking about the mechanics of actually publishing controversial pamphlets.

I’ve been reading Edward Sexby’s Killing Noe Murder for class this week, and it got me thinking about the mechanics of actually publishing controversial pamphlets.

Sexby was born around 1616 and served under Oliver Cromwell in his Ironsides during the early 1640s. By the time the New Model was formed in 1645, he was serving under Fairfax and went on to play an important role in the radicalisation of the army during the later 1640s. He famously set out his political views on the first day of the Putney debates:

The cause of our misery is upon two things. We sought to satisfy all men, and it was well; but in going about to do it we have dissatisfied all men. We have laboured to please a king and I think, except we go about to cut all our throats, we shall not please him; and we have gone to support an house which will prove rotten studs — I mean the Parliament, which consists of a company of rotten members.

After Putney, Pride’s Purge and the regicide, Sexby became an important figure for the Commonwealth and went to Bordeaux to try to influence his fellow Protestant Frondeurs and support them in their struggle. By 1655, though, like many fellow supporters of the Good Old Cause, he had fallen out of love with Cromwell and the Protectorate. He was involved in the plot by Miles Sindercombe to assassinate Cromwell in early 1657.

After the plot failed, Sexby – who was at this point in the Netherlands – wrote a pamphlet called Killing Noe Murder, giving biblical and classical humanist justifications for why Cromwell was a tyrant and could lawfully be killed. Although there is some debate about the extent of involvement, it seems likely that Sexby took the lead in writing it but perhaps in consultation with Silius Titus, the Presbyterian representative of the royalists Sexby had allied himself with against Cromwell. He introduced the pamphlet with this sardonic preface:

May it please your Highness,

How I have spent some hours of the leisure your Highness has been pleased to give me, this following paper will give your Highness an account. How you will please to interpret it I cannot tell; but I can with confidence say my intention in it is to procure your Highness that justice nobody yet does you, and to let the people see the longer they defer it, the greater injury they do both themselves and you. To your Highness justly belongs the honour of dying for the people; and it cannot choose but be unspeakable consolation to you in the last moments of your life to consider with how much benefit to the world you are like to leave it. ‘Tis then only, my Lord, the titles you now usurp will be truly yours. You will then be indeed the deliverer of your country, and free it from a bondage little inferior to that from which Moses delivered his. You will then be that true reformer which you would be thought. Religion shall be then restored, liberty asserted, and parliaments have those privileges

they have fought for.

The pamphlet seems to have arrived in London by 18 May. The Publick Intelligencer reported on that day that “divers abominable desperate pamphlets” had been scattered about the streets, including at Charing Cross and other places in the City.

The former Leveller John Sturgeon (formerly a member of Cromwell’s life guard, but since the mid-1650s an opponent of the Protectorate) was arrested on 25 May with two bundles of copies on him – about 300 in all. Two days later a search was made of St Catherine’s Dock and seven parcels with 200 copies – 1,400 in all – were found in the house of Samuel Rogers, a waterman. A bundle of 140 found near steps of a house. So perhaps 2,000 were taken out of circulation.

Many more did get circulated, though. John Thurloe wrote to Henry Cromwell on 26 May enclosing a copy:

There is lately a very vile booke dispersed abroad, called Killinge noe murder. The scope is, to stirre up men to assassinate his highnes. I have made search after it, but could not finde out the spring-head thereof. The last night there was one Sturgeon, formerly one of his highness’s life-guard, a great leveller, taken in the street, with two bundles of them under his arme. The same fellow had a hand in Syndercombe’s buissines, and fledd for it into Holland, and is now come over with these bookes. I have sent your lordship one of them, though the principles of them are soe abominable, that I am almost ashamed to venture the sendinge it to your lordship.

Thurloe’s assistant Samuel Morland wrote to John Pell at the start of June that:

There has been the most dangerous pamphlet lately thrown about the streets that ever has been printed in these times. I have sent you the preface, which is more light, but, believe me, the body of it is more solid; I mean as to showing the author’s learning, though the greatest rancour, malice, and wickedness that ever man could show – nay, I think the devil himself could not have shown more.

People paid up to 5 shillings to get hold of copies. A copy even got thrown into Cromwell’s coach.

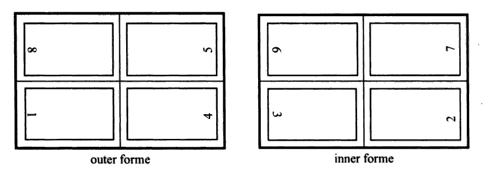

So how did Sexby and his accomplices achieve this? The first step was maximise the numbers who could have read Killing Noe Murder had. The pamphlet is 16 pages of quarto, and hence made up of two sheets of paper. Each set of 8 pages would have been printed as follows: the numbers represent page numbers in the final book.

It was printed on cheap paper – possibly ‘pot paper’, which in the 1620s had sold for between 3s. 4d. and 4s.6d. a ream. A ream contained 500 sheets, so one ream would have supplied 250 copies of the book. The 2,000 copies confiscated by the authorities would hence have cost at least £1 for Sexby and his accomplices to commission. Of course this does not include printer’s costs: by way of comparison, in 1655 Sturgeon had paid the radical printer Richard Moone 40 shillings for 1,000 copies of A Short Discovery of his Highness the Lord Protector’s Intentions. This was 8 pages long so a work double the size might have cost 80 shillings, or £4, for 1,000 copies. Assuming on top of the 2,000 confiscated copies that perhaps another 1,000 or 2,000 copies did survive and go into circulation, the whole enterprise might have cost Sexby £12 to £16.

Parcels of the pamphlet would then have been shipped across to London. Thurloe ordered a search of Dutch boats but had no luck in finding which skipper had shipped them over. It seems likely that John Sturgeon was Sexby’s London agent when it came to receiving and distributing copies. He had fled to the Netherlands after being involved in Miles Sindercombe’s failed plot to kill Cromwell earlier in 1657, so probably accompanied the pamphlets over to England from Amsterdam.

When it came to scattering copies about London’s streets, it’s impossible to know exactly how Sturgeon achieved this. However, it seems likely that he drew on radical political and religious communities within London. Sturgeon was a member of the Baptist church of Edmund Chillenden, which met at St Paul’s. In the 1630s, Chillenden had been involved with John Lilburne in distributing subversive puritan literature, and had subsequently been involved in army politics with Sexby. It seems plausible that his church was the centre for a number of London-based Levellers and Baptists whom Sturgeon may have mobilised to help. Someone else arrested along with Sturgeon was Edward Wroughton, a haberdasher who was a member of Thomas Venner’s Fifth Monarchist congregation at Coleman Street. Members of this church were mostly young men and apprentices, who would be likely candidates for dispersing the pamphlet during the middle of the night. So it’s possible too that a network of congregations played a part in helping Sexby.

Killing Noe Murder had an impact out of proportion to its size and the number of copies distributed. It became a major talking point and the Protectorate took significant steps to take it out of circulation and arrest its conspirators. Sadly for Sexby, he was arrested after returning to London in June 1657 to foment further assassination attempts. While being held in the Tower of London he confessed authorship of Killing Noe Murder. He died there in January 1658.

My illustration is of course of the Master DI Sam Tyler John Simms as Sexby in The Devil’s Whore. For more on Sexby and Killing Noe Murder:

- Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. [subscription or Athens access needed]

- ‘State Papers, 1657: May (6 of 6)’, A collection of the State Papers of John Thurloe, volume 6: January 1657 – March 1658 (1742), pp. 315-329.

- James Holstun, Ehud’s dagger: Class Struggle in the English Revolution (London and New York, 2000), ch. 8.

- C.H. Firth, ‘Killing No Murder’, English Historical Review (1902), pp. 308-311. [subscription or Athens access needed]