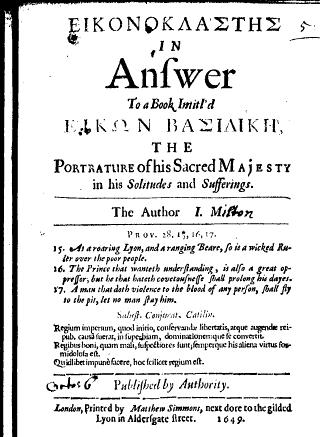

Recycled woodcuts

A recent post at Mistris Parliament, with its woodcut of the leatherseller Praisegod Barebone preaching from a tub, reminded me about the provenance of that particular image. Below is the woodcut of Barebone, which is taken from the frontispiece of John Taylor’s New Preachers, New (London, 19 December 1641). The poor quality of the paper has meant text from the other side of the page has bled through:

But this woodcut actually appeared on the front of at least four pamphlets. The first appearance was in June 1641 on the front cover of another of John Taylor’s works, A Swarme of Sectaries (London, June 1641). It seems to have been designed specifically to match the content, which was a description of London’s various “mechanic preachers” – in other words, Independent preachers without a benefice.

The sign to the right shows that the preaching is taking place in the Nag’s Head in Coleman Street, supposedly a notorious gathering place for independent congregations. “Sam How” is Samuel Howe, a cobbler who had actually been dead for almost a year by the summer of 1641, but whose notoriety was clearly still news-worthy.

The woodcut was then reused in October on the front of The sermon and prophecie of Mr. James Hunt (London, 9 October 1641). This time the sign was cropped, and the top of the block was chiselled away to allow type to spell out the name of yet another preacher, a farmer from Kent:

The woodcut then made a third appearance in December on the back page of John Taylor’s Lucifers Lacky (London, 4 December 1641), almost as an afterthought. By this point, the quality of the woodblock was getting significantly worse. Nor was the illustration as well matched to the pamphlet’s content.

After being used for New Preachers, New on 19 December, it then appeared a fifth time on the front of A tale in a tub, or, A tub lecture as it was delivered by Mi-Heele Mendsoale (London, 21 December 1641), a mock sermon also by John Taylor:

We know very little about who made woodcuts like these, or exactly how they fitted into the communication circuit in which cheap pamphlets existed. Were woodcut makers independent craftsmen who offered their services to printers? Or were they based in print houses directly? Was it even a specialised trade, or was it carried out as part of a wider range of woodworking or printing skills? How many people were involved in cutting woodcuts? Who chose and designed the illustration – the author, the printer, or the bookseller? So little evidence about the skill survives for the seventeenth century that it is hard to tell.

However, there are things that can be deduced about the trade from woodcuts like the one above. The first half of the seventeenth century appears to have seen an increasing use of illustrations for cheap print, increasingly matched to the content. From the mid-1610s, pamphlets about murder, natural disasters and other strange news often had one-off illustrations cut to match. This implies that readers were starting to demand illustrations: pamphlets with woodcuts may have sold better, or been hung up outside the shop to tempt in passing trade. It also implies that authors, printers and booksellers could afford to commission new woodcuts for one-off works. The biggest cost of any book was normally the paper it was printed on, so compared to that the cost of a woodcut for a short quarto pamphlet with a print-run of perhaps 200-1,000 copies must have been outweighed by the benefits.

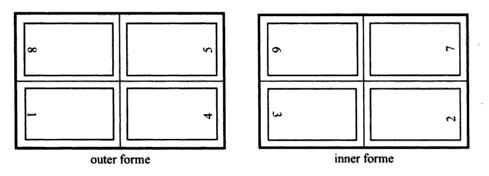

So why does this woodcut crop up so many times in 1641? Well, partly because anti-separatist literature sold well. But why not commission new woodcuts for each pamphlet? A clue might lie in the authors, printers and booksellers of all four pamphlets:

- New Preachers, New. Written by John Taylor, for an anonymous bookseller and printer.

- Swarme of Sectaries. Written by John Taylor, again for an anonymous bookseller and printer. However the imprint declares it was “printed luckily, and may be read unhappily, betwixt hawke and buzzard”. This is very similar to the fictitious imprint of The Downefall of Temporizing Poets (London, 1641), which declared that it was “printed merrily, and may be read unhappily, betwixt hawke and buzzard”.

- The sermon and prophecie of Mr. James Hunt. Purports to be by Hunt, but is probably a satire – perhaps even by Taylor, who had something of a specialisation in anti-separatist works. Printed for the bookseller Thomas Bates, a shady operator specialising in cheap and often scandalous pamphlets. He was based at the Old Bailey outside the City limits, and was often in trouble with Parliament for seditious printing.

- A tale in a tub. Written by John Taylor. Printed, according to the imprint, “in the yeare when Brownist did domineare”. What is interesting about this use of the woodcut is that it was not the first edition of the pamphlet. The first version was printed in 1641, without any illustration. This suggests it was a good seller that was repackaged along with the woodcut to drum up additional sales.

- Lucifers lacky. Written by John Taylor, printed for John Greensmith. Like Bates, in 1641 he got into trouble with the Commons for printing scandalous pamphlets.

Both Bates and Greensmith often sold pamphlets printed by Bernard Alsop and Thomas Fawcett, two printers who also operated on the fringes of the law. They too were hauled before Parliament on a number of occasions in 1641 for illicit printing. Works with their imprint are distinguished by their worn type and hasty typesetting. A detailed analysis of the ornaments and typefaces, comparing them to works known to be printed by Alsop and Fawcett, might reveal more about whether these five works were printed by them. For example, Lucifers Lacky uses an ornament identical to that used in a work called The Vertue of Sack, printed by Alsop:

If they were printed by Alsop and Fawcett, it may indicate that they were trading in tough circumstances. Despite the explosion of print in 1641, operating in illegal or semi-legal ways may have meant more financial risks. Short 8-page quarto pamphlets could be printed relatively quickly to make a quick sale. If they didn’t sell, the losses were relatively minimal. So the recycling of woodcuts may indicate that Alsop and Fawcett were trying to preserve their bottom line: either by speeding up the process of printing (saving the time that would have been spent commissioning special illustrations), or minimising the cost of production by reusing a woodblock hanging round the print house. Or perhaps it indicates that books needed in 1641 needed illustrations to stand out from the huge numbers of competitors: perhaps any old woodcut would do, so long as it caught the eye.

If they are by different printers, it has a rather different impliation. It would mean that printers were sharing woodblocks, which would point to a degree of cooperation amidst financial competition. And equally if John Taylor wrote all five, it is possible perhaps that it was he who commissioned the woodblock, and requested that his booksellers use it for particular pamphlets. But I have a suspicion the answer may well lie with Alsop and Fawcett.

I’ve been reading Edward Sexby’s

I’ve been reading Edward Sexby’s