For Ada Lovelace Day: Jane Coe

Ada Lovelace Day exists to raise the profile of women working in the fields of science, technology, engineering and mathematics. This post is about a woman who played a significant role in the printing trade in seventeenth-century London: Jane Coe.

As Sarah Werner has made clear – in another post for Ada Lovelace Day – women played a significant role in trades related to books and printing in early modern London. However, their role can often be obscured by the slender evidence that survives about early modern printers and booksellers. Even where evidence does survive, it has to be read carefully: like all trades of the period, printing was dominated by men, and the terms in which female printers are described by contemporaries can underplay their importance.

Jane Coe is no exception. We know a lot about what she printed. The English Short Title Catalogue lists over seventy titles printed with either “Jane Coe”, “I. Coe” or “J. Coe” on the imprint. Some of these were serials that ran over a number of years, so the actual number of books she printed must run into the tens of thousands. In the main, these were short quartos: printed versions of letters, satirical pieces accompanied by woodcuts, news pamphlets giving accounts of battles and negotiations, and above all newsbooks. Their emphasis is overwhelmingly Parliamentarian. However, we know very little about Jane herself.

Jane’s original name may have been Jane Bowyer. On 27 December 1634, a Joane Bowyer married Andrew Coe in the church of St George the Martyr in Southwark.

Andrew was an trainee printer who was served an apprenticeship with the Stationers’ Company. He was not made free until 1638, having been bound to his master George Miller in 1630. This makes a 1634 marriage seem, on the face of it, unlikely. Under the terms of their indentures apprentices were not allowed to marry. To do would technically prevent them from qualifying for their freedom. However, there were good reasons why apprentices might break the rules. One is financial gain. It is not uncommon to find apprentices marrying well-heeled widows (sometimes the wives of their masters), presumably calculating that it would be financially worth their while or that the widow’s resources would enable them to purchase their freedom by redemption. The other is love.

If this is Jane – and I can find no other marriage records for an Andrew Coe – then we have no way of knowing what prompted their marriage, or whether they lived together afterwards. The next time they appear in the records is in the parish registers of St Giles Cripplegate, where Andrew had set up business. We can hazard a guess about the family’s financial status by looking at the type he used, which was old and worn. He presumably did not have enough capital to buy a new set, and either inherited an old set or purchased it from another printer.

Cripplegate was a parish just outside the City walls, and with a high concentration of printers and booksellers. Grub Street, soon to become synonymous with a certain kind of printed book, is within the parish boundaries. Many of its parishioners also seem to have had puritan leanings. In 1641 there were conflicts between the parish and its high Anglican vicar and churchwarden, William Fuller and Thomas Bogh. Bogh went as far as to assault a Parliamentary messenger sent to enforce an order to remove the parish’s altar rails. So it is possible, especially given the subsequent output of their press, that Andrew and Jane’s religious leanings ran this way, although again there is no way of proving it.

In February 1640, the couple had a son, named after his father:

Jane, again, is entirely absent from this record. All that is recorded is the name of her husband and his profession. However, it’s clear that she must have had some involvement in the business. At some point around the end of June 1644, her husband died, and Jane took over the running of the press. An illustration of how difficult some historians have found it to accept that this was possible can be found in H. R. Plomer’s Dictionary of Printers for the period, which says this about Andrew’s death:

The younger Andrew was six years old at this point, and presumably in no position to run anything in relation to the business. And yet Plomer’s assumption – despite the fact that it was Jane’s name that appeared on the imprints of the press’s books after this date – seems to have been that the couple’s son must have been the real head of the operation.

After the older Andrew’s death, Jane continued to print the same kind of books that the press had already become known for. Between 1644 and 1647 she was involved in the production of several newsbooks, including Perfect Occurrences, The Moderate Messenger, and The Kingdomes Scout. In 1645 she took on an apprentice, Samuel Houghton, who came from Mowsley near Market Harborough. It was Jane whose name appeared in the Stationers’ Register for many of her titles, and Jane who presumably took the copy there for the licenser to approve.

What happened to Coe after the 1640s is not clear. At some point, the business was finally handed over to her son: his name appears on a few imprints in the 1660s, by which stage he would have been in his twenties. His name also appears at various points before that, with the formulation “Printed by J. Coe and A. Coe”. So it does seem clear that Jane’s eventual aim was to set her son up in her and her husband’s trade. By October 1664, Andrew was firmly ensconced in Cripplegate, had a wife named Hannah, and had a son (a third-generation Andrew):

Again, however, the surviving evidence about Jane is very slim. I can find no record of Jane’s death anywhere in the registers of St Giles Cripplegate or other London parishes. No wills survive for either her or her husband.

So Jane remains something of an enigma. She was clearly something of a publishing force in the world of cheap print in the 1640s, but tantalisingly little remains about who she was. I hope this post brings her achievements to a slightly wider audience.

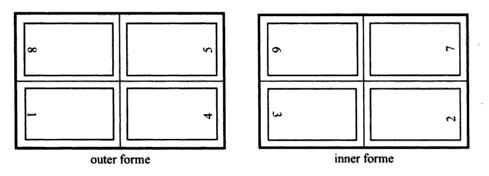

For more on the Coes’ business, the best work is the recent article by Sarah Barber, ‘Curiosity and Reality: the context and interpretation of a seventeenth-century image’, History Workshop Journal vol.70 (2010), pp.21-46. Some of the details above I owe to this article, although others are based on my own trawls of Jane’s books and of London parish registers.

I’ve been reading Edward Sexby’s

I’ve been reading Edward Sexby’s