Bookshelves are not the most obvious thing that comes to mind when you think about information technology. But the word technology is actually a very appropriate description: the word “τέχνη” from which it derives means craft or art, which is apt given the skills that go into producing shelves. For early modern readers, and even readers today, bookshelves were and are one of the most important methods for storing and accessing information. And bookshelves are not just passive, functional pieces of wood, metal or plastic that provide a neutral home for books to sit on. The other Greek word from which technology derives – “λογία” – means saying or utterance, and this expressive, constitutive aspect of technology is important to bear in mind. As with any other material aspect of a book, bookshelves mediate a reader’s experience of a text.

This was certainly the case for many early modern readers. Michel de Montaigne kept his book collection in the third storey of a tower, which allowed him unfettered views not just of his geographical domain but also his textual and intellectual domain:

My library is round in shape, squared off only for the needs of my table and chair; as it curves round it offers me at a glance every one of my books ranged on five shelves all the way along. It has three splendid and unhampered views and a circle of free space sixteen yards in diameter.

You can see a reconstruction of Montaigne’s library here. The arrangement of shelves allowed him a remarkable intellectual freedom to wander through his books:

Here I leaf through now one book, now another, without order and without plan, by disconnected fragments. One moment I muse, another moment I set down or dictate, walking back and forth, these fancies of mine that you see here.

Sir Robert Cotton’s library helped to order his reading in a different way. At some point between 1620 and his death in 1631, Cotton arranged his extensive collection of rare manuscripts into fourteen cabinets, each mounted by a bust of a famous classical figure such as Julius Caesar, Cleopatra, Caligula or Nero. Kevin Sharpe’s reconstruction of how this might have looked can be seen here.

Unlike other collections, this meant his library was not organised by subject. Nero, for example, contains the Lindisfarne gospels alongside collections of royal diplomatic correspondence. Julius contains Ælfric’s Lives of Saints alongside a copy of the charges brought against Cardinal Wolsey.

Cotton allowed liberal borrowing from his library by friends and colleagues, making it both a private and semi-public collection. But only Cotton and his libarian would have had the knowledge to find books quickly. As Kevin Sharpe has put it:

Cotton and his books went together and contemporaries had to know Cotton before they knew much about the contents of his manuscripts.

For Cotton, then, bookshelves were a way of organising other readers’ experience of his books, as well as his own.

Samuel Pepys was another seventeenth-century reader whose bookshelves helped to mediate his reading. In the 1660s Pepys drew on his contacts as a naval administrator to procure the services of Thomas Simpson, a joiner at the Royal Naval Dockyard in Woolwich. Simpson was first employed to build a closet for clothes, but in 1666 Pepys commissioned him to build a set of bookcases for his growing collection of books. Practical considerations seem to be what first motivated his decision to build the shelves:

23 July 1666. Up, and to my chamber doing several things there of moment, and then comes Sympson, the Joyner; and he and I with great pains contriving presses to put my books up in: they now growing numerous, and lying one upon another on my chairs, I lose the use to avoyde the trouble of removing them, when I would open a book.

The need to manage growing amounts of information, or otherwise risk overload, seems to have been a common impulse for readers with the money to afford book collections. Later, during his retirement, Pepys devoted considerable time to cataloguing his library, employing Paul Lorrain and his nephew Jackman as librarians to help him.

But there were also more sensual pleasures to be had from building shelves:

10 August 1666. Thence to Sympson, the joyner, and I am mightily pleased with what I see of my presses for my books, which he is making for me.

In Pepys’s case, pleasure could be had not just from organising his collection, but from making it beautiful too:

24 August 1666. Up, and dispatched several businesses at home in the morning, and then comes Sympson to set up my other new presses for my books, and so he and I fell in to the furnishing of my new closett, and taking out the things out of my old, and I kept him with me all day, and he dined with me, and so all the afternoon till it was quite darke hanging things, that is my maps and pictures and draughts, and setting up my books, and as much as we could do, to my most extraordinary satisfaction; so that I think it will be as noble a closett as any man hath, and light enough – though, indeed, it would be better to have had a little more light.

You can make out the portraits and a map in this engraving of Pepys’s later house at Buckingham Street in 1693.

A finely decorated library was undoubtedly an important status symbol for Pepys; but the aesthetics of his library were also crucial. He took great pleasure in commissioning shelves that were intricate and beautiful, as well as practical. His bookcases were made of oak and glass-fronted, with the main section holding folio size books. The lower sections use sliding glass panels for smaller books. The Pepys Library site hosted by Magdalene College has a good selection of images: 1, 2, 3.

Books also needed to look right on the shelf. Pepys was adamant that the books should be arranged by height, even specifying in a codicil to his will that after his death:

8 thly That the placing as to heighth be strictly reviewed and where found requiring it more nicely adjusted.

Even the books themselves were turned into objects of beauty. They were expensively bound, stamped with Pepys’s crest, had bookplates in the front and endplates at the back. You can see Pepys’s bookplate here.

So what difference did bookshelves make to these three early modern readers? We shouldn’t underestimate the functional aspect of shelves. As private book collections grew, they needed to be stored somewhere. But for Montaigne, Cotton and Pepys, bookshelves also provided different experiences of reading. They allowed Montaigne to wander through his collection, whereas for Cotton they helped to close it off to others. Pepys, meanwhile, derived both pleasure and status from his bookcases.

The growth in recent years of a new history of the book has resulted in a much greater focus on the material aspect of texts, such as the paper they are printed on, the typeface they use, or the ink they are printed with, and on the ways in which early modern readers approached and constructed their reading. In Don McKenzie’s words:

A book is never simply a remarkable object. Like every other technology it is the product of human agency in complex and highly volatile contexts which a responsible scholarship must seek to recover if we are to understand better the creation and communication of meaning as the defining characteristic of human societies.

As a product of human agency themselves, bookshelves too have their place in the history of books and reading.

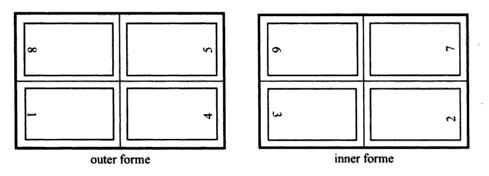

My illustration is from Claude du Molinet’s “Le Cabinet de la Bibliothèque de Sainte Geneviève” (Paris, 1692). AN465647001, © The Trustees of the British Museum.

I’ve been reading Edward Sexby’s

I’ve been reading Edward Sexby’s