Describing the news

How do you describe what “news” means? If you try define it – whether simply as new information, or as information about current affairs presented through various media – it renders it almost banal. Equally, to analyse in detail the range of overlapping shapes and identities that news as a concept can take is also very difficult.

And yet like art, or pornography, we all know what news is when we see it. Living in a news-saturated culture, almost without thinking we use a range of linguistic and conceptual shortcuts to make sense of what we understand by news. Many of these draw inspiration from the communication circuit in which news exists. Titles are one such short-cut. We know instinctively what we will find in the Daily Mail – “asylum seekers cause cancer” – just as much as we know what to expect from the Sun – “Tracy, 18, says she’s supporting David Cameron because of his policies on tax breaks for glamour models”. We are so familiar with some titles that we give them nicknames: the Thunderer, the Grauniad, the Indie.

Authors are another shortcut. The names of columnists like Polly Toynbee or Richard Littlejohn will forever be associated with particular styles of writing and world-views. Mention “Dave Spart” to any Private Eye reader and they will instantly call to mind the kind of left-wing pundit the term satirises. Verbal and sartorial tics single out newsreaders and the editorial line they represent much more quickly than any kind of analytical language. John Snow’s ties are Channel 4 News in the same way that Martin Bell’s white suit symbolised something about his particular style of foreign news reporting. We know what is going to happen when Trevor McDonald utters the words “and finally”.

Paper size is yet another. We have tabloids, and we have broadsheets, and the two have very diffierent associations, which is perhaps why the Guardian caused such a fuss when it moved to the new Berliner-style format a while back. The chances are these two terms will remain in use long after newspapers – in the sense of news printed on paper – have died out. This is certainly true of another term linked to the production of papers. Fleet Street is still the collective term for the British press thirty years after Rupert Murdoch killed off any physical association between that area of London and journalism. Readers can also define particular types of news. “Disgusted of Tunbridge Wells” lives on fifty years after the term was first popularised, despite the likelihood that very few people remember its origins.The regulars of the BBC News “Have Your Say” section are, for me at any rate, swiftly becoming Disgusted of Tunbridge Wells 2.0.

Our understanding of what news means is thus deeply shaped by and rooted in the cultural forms and agents that bring it to our attention. So perhaps we shouldn’t be surprised that people in mid-seventeenth century England – who lived in an equally news-saturated culture – used the same kind of techniques to make sense of news as it evolved in front of them. What follows is a scattered account of various primary sources I have come across that, in some way or another, use various stages in the news market’s communication circuit to try to analyse or define the concept of news in civil war England. Rather than try to analyse them at this stage, I have simply described them. (This may or may not turn into a more considered post at some point).

As quickly as newsbooks were born, their titles took on an identity of their own. The 1642 tract A Presse Full of Pamphlets traced the corruptive influence of print to the invention of the first ever newsbook:

But in hope of more gain to himself by undoing of others, put the first Copy of the Diurnall Occurrences that was printed to a Printer, and then came all other things true and false to the Presse.

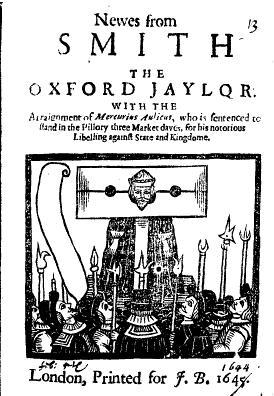

From this point on, individual titles started to stand for particular styles of writing and different shades of politics. Here for example is the frontispiece to a satirical pamphlet poking fun at the early royalist newsbook Mercurius Aulicus:

AN352667001, © The Trustees of the British Museum

A reader has written “Sir John Birkinhead” [sic] underneath the woodcut, but it is worth noting that the original pamphlet didn’t need to name the newsbook’s editor: the title was enough. During the 1640s newsbooks were as much the subjects of pamphlet literature as politicians or generals. The image below, which shows the front pages of two warring pamphlets laid out alongside each other, is a good example:

For a time there was even a trend for editors to bring out titles diametrically opposed to their enemies, and signified as such by having the prefix “Anti” in their title. Probably the most meta and paradoxical of these is Mercurius Anti-Mercurius, which tries to do itself out of a job even in its very title:

In layout and style this is (deliberately) almost identical to real newsbooks, from the title and series numbering through to the poem on the front page; and yet it proclaims itself not to be a newsbook. Pamphlets like this are an indication of how quickly the innovations of the 1640s – bear in mind the newsbook was only invented in 1641 – became normalised and integrated into the political and cultural vocabulary of contemporaries.

Nevertheless, editors themselves also became a recognisable shorthand for certain types of journalism. Of all the newsbook editors, Henry Walker probably attracted the most mud-slinging. Royalist newsbooks developed a range of nicknames for him, including ‘Beelzebubbs brindled Ban-dogge’, ‘Sirrah saffron-chapps’, ‘Athiestical liar’, ‘Parliaments News-Monger’, and ‘Rusty Nuncio’ (the second and last a reference to his red hair). Ever since, Walker has been associated with a kind of pedestrian journalism that relies on press releases and official titbits rather than ‘real’ investigative scoops. This is to impose Victorian and twentieth-century categories of journalism onto a period in which “journalism” (if we can even use that word) meant rather different things, and is also a bit unfair on Walker. But informed contemporaries would probably have known what royalist editors were getting at when they presented Walker as the symbol of what they saw as an arrogant, godless Puritan regime.

The 1647 pamphlet A fresh whip for all scandalous lyers went so far as to assemble a mock-encyclopedia of newsbook editors. Its primary aim was probably satirical, so it is problematic to seek to match the personalities it describes too closely to real editors. As a source of biographical details it may well be inaccurate. Nevertheless, for contemporaries to have found it funny it must have at least had the ring of truth. Here are some extracts from its pastiches of Samuel Pecke and Henry Walker:

I must beginne with the Diurnall Writer first… I may not unfitly tearme him to be the chief Dirt-raker, or Scafinger of the City; for what ever any other books let fall, he will be sure, by his troting horse, and ambling Bookselers have it convey’d to his wharfe of rubbish.

The Perfect Occurrence Writer… his whole face is made of Brasse, his body of Iron, and his teeth are as long as ten-penny nayles… Witnesse how many times hath he taken and killed Prince Rupert, and Prince Maurice, and Sr. Ralph Hopton: he hath an excellent faculty to put a new title to an old book, and he will be sure to put more in the Title page than is in all the booke besides.

The means through which newsbooks were produced and distributed also seem to have become associated with particular definitions of news. The title of one early critique from 1642 name-checks everyone involved in this process:

This is not to suggest that titles, editors, printers and sellers were the only language through which contemporaries were able to analyse and discuss the news market of the 1640s. There are various sophisticated critiques of newsbooks and the news industry from many contemporaries. My favorite of these is probably still this jaundiced editorial from an early edition of the Briefe Relation, one of the first ‘official’ newsbooks issued by the Commonwealth after the execution of Charles I:

To have no Newes is good Newes, it is a symptome of a placid and quiet state of affaires. The subject of newes which is most enquired for, is for the most part of Wars, Commotions, and Troubles, or the Composing of them.

Even for the lay reader, though, there were other ways to approach the concept of news than its constituent actors. The woodcut below – from Matthew Hopkins’s 1647 pamphlet A Discovery of Witches – is famously used to illustrate many textbooks’ accounts of early modern witchcraft:

But almost unnoticed at the bottom left, it also personifies news as a bit-part character in the form of a weasel: