Images of regicide

by mercuriuspoliticus

With the 360th anniversary of the execution of Charles I coming up on Friday, I thought I would have a look at what the internet has to offer on images of the regicide.

While Charles’s reputation has been the subject of immense debate, pictures of his execution have tended to be remarkably consistent over the years. Immediate reactions to the regicide – mostly printed abroad, for obvious reasons – tended (like the frontispiece of the Eikon Basilike) to emphasise Charles as martyr. Here, for instance, is an etching from a Dutch broadside of 1649, Historiaels verhael… Carolvs Stvarts, Coningh van Engelandt, Schotlandt, en Yerlandt.

AN257700001, © The Trustees of the British Museum

It’s fairly gruesome: you can see Charles’s body spurting blood from its severed neck. From left to right you can see Thomas Juxon, Colonel Francis Hacker, Colonel Matthew Tomlinson and the executioner. But in the apotheosis scene above, you can also see Charles’s spirit ascending to heaven.

Very similar, but without the apotheosis, is this German engraving from 1649, Endhauptung der Konigs in Engelandt.

AN151032001, © The Trustees of the British Museum

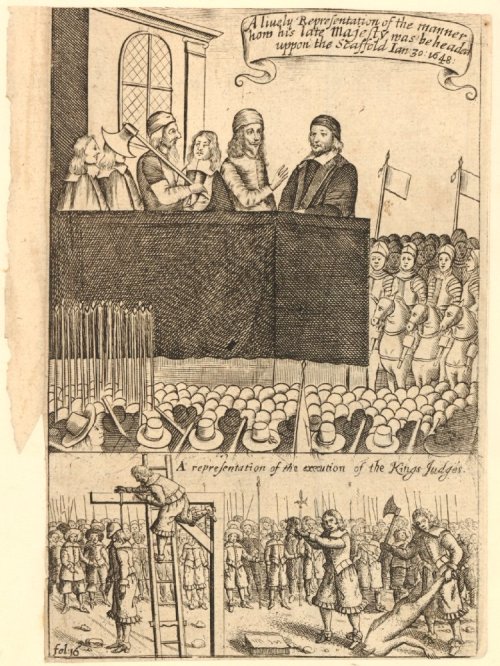

This kind of image persisted and was reinforced after the Restoration. Below is A lively Representation of the manner how his late Majesty was beheaded uppon the Scaffold, which probably dates from around the execution of various regicides in the early 1660s. At the top of the etching, Charles waits in dignity for his fate, while below one of the regicides is hanged, drawn and quartered.

AN260225001, © The Trustees of the British Museum

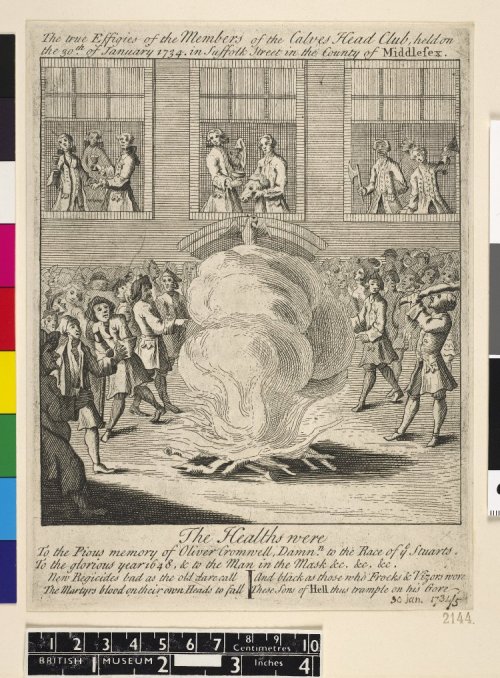

For much of the eighteenth century this kind of representation of Charles’s execution persisted. While Whigs and Tories battled over the history of the civil wars and rewrote and redeployed the key events and figures of the period to suit their ideologies, for the most part Jacobites seem to have resurrected the martyr cult while most orthodox Whigs remained horrified by the actual execution. But the more radical were still happy to celebrate the anniversary of the regicide: The True Effigies of the Members of the Calves Head Club from 1735 shows a mob gathering around a bonfire outside the Golden Eagle tavern in Suffolk Street, near Charing Cross, to celebrate.

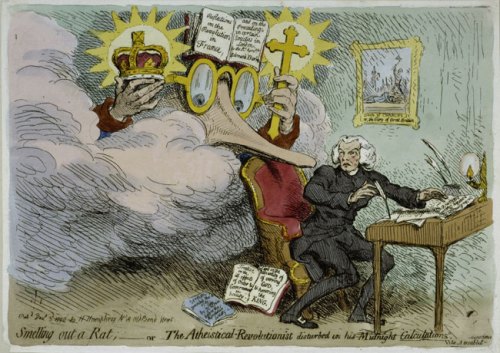

By the end of the eighteenth century, though – fuelled in part by events in France – depictions of the regicide were becoming more unstable. Here is a print by James Gillray from 1790, Smelling out a rat; or the atheistical-revolutionist disturbed in his midnight “calculations”.

The figure at the desk is Richard Price, a radical dissenter. He sits below a portrait of the execution of Charles, writing an essay called “On the Benefits of Anarchy Regicide Atheism”. Smelling him out is a caricature of Edmund Burke carrying a crown in one hand and a cross in the other. On one level the meaning is straightforward: the painting of Charles is labelled “Death of Charles I, or the Glory of Great Britain”. But Burke doesn’t exactly come out of the print wonderfully, either.

Still, even in the Victorian era Charles’s execution was often seen even by those who sympathised with Cromwell as an understandable but regrettable step. Great efforts were made to explain the actions of Cromwell and other regicides as a temporary blip in constitional propriety, prompted more by the evil of royalist enemies than by a failure of character by Cromwell. Radical and nonconformist images of the civil wars seem to have focused on more positive rehabilitations of Cromwell than on debunking the idea of Charles as a martyr king. I haven’t seen any images from the nineteenth century that go down this route. What I have found is some wonderful images of martyrdom:

Illustration from Charlotte M. Yonge Young Folks’ History of England (Boston: D. Lothrop & Co., 1879)

Painting by Ernest Crofts of Charles being led to his execution.

Closer to the present, no account of images of the regicide would be complete without the moving – pun intended – images of the execution in Ken Hughes’s 1970 film Cromwell. If you studied this period at school in England during the 1980s, then probably the mere mention of the phrase “a ciiii-vil war?” will be enough to transport you back to Proustian memories of the film, but if you haven’t seen it here is a clip I found on Youtube of the climactic scene. Alec Guinness as Charles goes resignedly to his fate, while Richard Harris as Cromwell looks moody. But if nothing else it shows the persistence of images of Charles as martyr.

[…] Mercurius Politicus notes with a nice selection of images, today is the 350th anniversary of Charles I’s […]

[…] The image of Charles the martyr persisted for many years after the Restoration of Charles I. The Society of King Charles the Martyr still exists today. More on Charles as martyr can be found in Andrew Lacey’s article on ‘Charles the First, and Christ the Second’ [Google Books]. The image of Charles persisted well into the nineteenth century and beyond: see a recent post of mine for some examples. […]

[…] consciousness. This much is well-known to eighteenth-century-ites. What is perhaps less well known (at least, to me until I read this post) is the fine historical drama Cromwell, which stars Sir Alec Guinness as Charles I. The following […]

Brilliant article.

Im writing on Charles II right now. you could have a look, and as a bonus, you can vote on whether I am total loser in a poll.

[…] Images of the regicide. […]

[…] erected at Whitehall. He gave a short final address, with the famous words for his principle of martyrdom — “a sovereign and a subject are clean different things” — then laid his […]